The Quran is believed to a revelation that the Prophet Muhammad, the founder of Islam, received from a monotheistic God, Allah. It is also the most important scared ure of Islam. The content of the Quran was originally relayed orally, but later it was recorded with materials such as leather, stone, parchment, palm leaf, bamboo, and fabric in attempts to permanently preserve Muhammad's prophecies. It is estimated that the Quran, manufactured in the form of a scared book, was introduced by Muslim merchants and missionaries after the 11th century, when Islam was transmitted into Southeastern Asian countries.

During the same period, powerful and influential individuals in other states such as Johor, Kelantan, and Terengganu also converted to Islam. This resulted in many Malaysian kingdoms being governed by Islamic law. As such, religious art work plays an important role in showing the expansion of the new Islamic civilization and religion throughout Malaysia.In Islamic Malaysia, the Quran was considered to be the most sacred book and also served as a collection of religious artwork that combined advanced technologies adopted from the Arab world. In particular, Qurans produced by renowned calligraphers and masters in regions from the Islamic cultural sphere, such as West Asia and Central Asia, were brought into Malaysia to represent the authority of Malay Sultans. The status of the Quran was also elevated in status by becoming a royal possession.

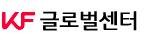

The Qurans sent to Malaysia are exhibited in the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia (IAMM), which is located in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. Only by looking at the Quran produced by the masters of the 19th century Qajar Dynasty of Iran can one truly see how much effort and labor was put into its creation (Picture 1, 2 and 3).In accordance with the Hadiths, which prevent deion of humans and animals, the Quran from the Qajar Dynasty do not contain deions of living beings. Instead, colorful flowers and vines are inscribed with an abstract and geometric style. The Hadiths are a record of Muhammad's deeds and teachings and are considered one of the most important sacred ures of Islam alongside the Quran.

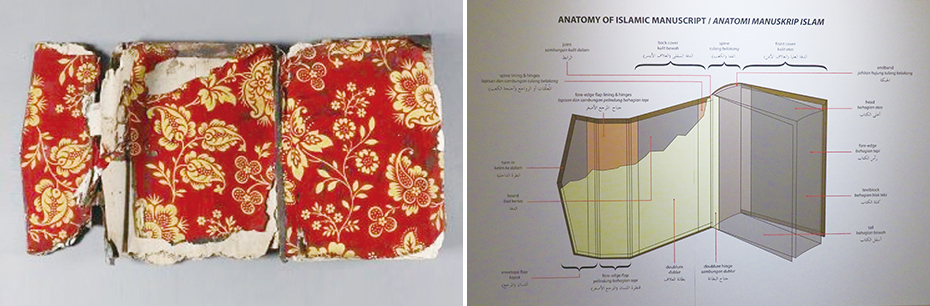

The Quran in Western Asia is typically decorated with flowers, clouds, and calligraphy, drawn in the form of pendent placed in the center of the cover. The rest of the cover, along with the four boundaries, are filled geometric patterns and shapes in an Arabesque style and ornamentations in the shape of flowered vines. These ornamentations were sometimes inlaid with gold plates or jewels. Gesso was also used to laminate the cover. Even in West Asia, the Quran started to appear in the form of a book with elaborate covers (as described above) and using certain book-binding techniques after the 16th century. It appears that these book-binding techniques were gradually transferred to Southeast Asia through Muslim missionaries.

After the 19th century, local merchants in Malaysia started to produce the Quran themselves. Particularly, the book-binding techniques used to produce the Quran in the northeastern state of Trengganu appear to be the most advanced in comparison to the techniques used in other states. According to a study, Qurans produced by the masters of Trengganu were highly sought-after at the time. The royal families of Palembang and the western states of Kalimantan and Pontianak owned Qurans produced by the Trengganu masters. An interesting fact is that, even today, many people from Trengganu are known for their beautiful Arabic calligraphy skills. In addition, many winners of Quran recitation contests are from Trengganu. Through this, it can be inferred that many Malay people residing in Trengganu have been passionate producers of religious artwork that is based on their religious faith.

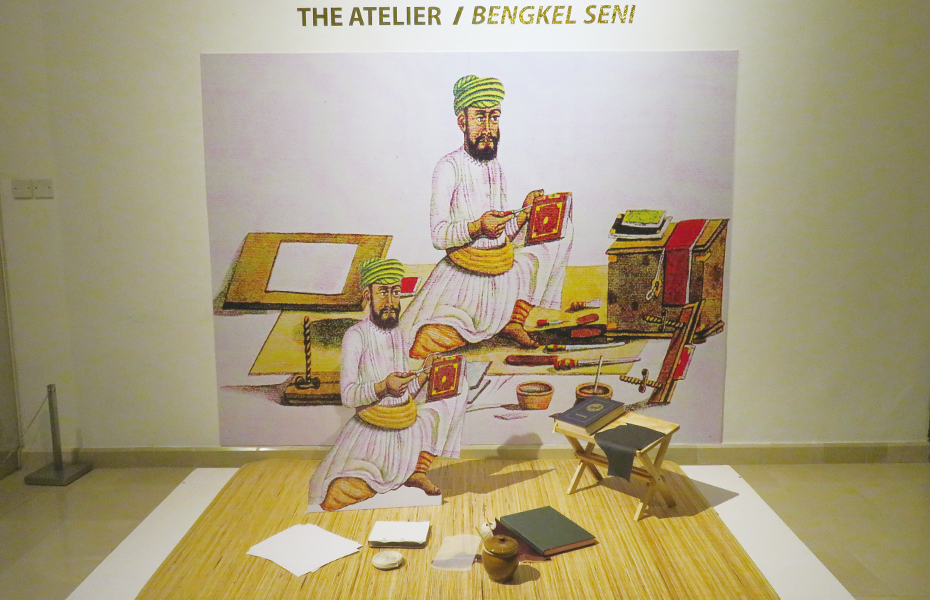

At the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, there is a Quran produced in Trengganu in the 19th century (Picture 3). With just a glance, one can see that it was produced using a unique book-binding technique that is distinct from that used for Qurans imported from West Asia. The Quran produced in Trengganu has a leather cover patched with fabric. The dyed-red fabric symbols representing plants are painted in gold and are positioned over the entire cover.

Instead of following the composition of the Quran produced in places like West Asia, the Qurans of Trengganu respects a basic composition that is compliant with the Islamic doctrines while also reflecting the local situation. For example, Indian cotton textiles were used for the cover, mostly produced in the region of Gujarat. Among 19th century Indian cotton textiles, cotton textiles produced in Gujarat were recognized for their beautifully-decorative patterns and outstanding quality, even being exported as far as China and other Southeast Asian countries. The fact that the Trengganu Quran was produced using imported materials to represent the local culture is a testament to the Malay masters' ingenuity.

Techniques such as the book-binding technique used to combine individual pieces of paper into one book and a book flap contraption used to allow an extended back cover to be folded over the front, covering the book like an envelope show that the Malay Muslim masters acquired the basic book-binding techniques developed in West Asia (Picture 3). Through such technical skills, they could keep the sacred prophecies of Prophet Mohammad safe. As such, the Quran is a work of art that demonstrates that the proliferation of Islam as well as highly-advanced technologies for book-binding.

Lastly, to help understand the religious values of the Muslim masters in their treatment of the Quran, I would like to share an excerpt from an 11th century textbook, which is also currently on display at Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, to summarize this essay.

“He who seeks (to acquire) this craft, requires;

(First) quick understanding, a good and sharp eyes, quick hands, avoidance of haste, and good sitting posture;

(Secondly) to be sociable and of good character”

-From Umdat al Kuttab wa ‘uddat dhawi al-albab(=Textbook on penmanship and tools of learning),

attributed to Ibn Badis(1016-1062 A.D.)-

KOREA FOUNDATION

KOREA FOUNDATION