Framing a Twist on Zombies

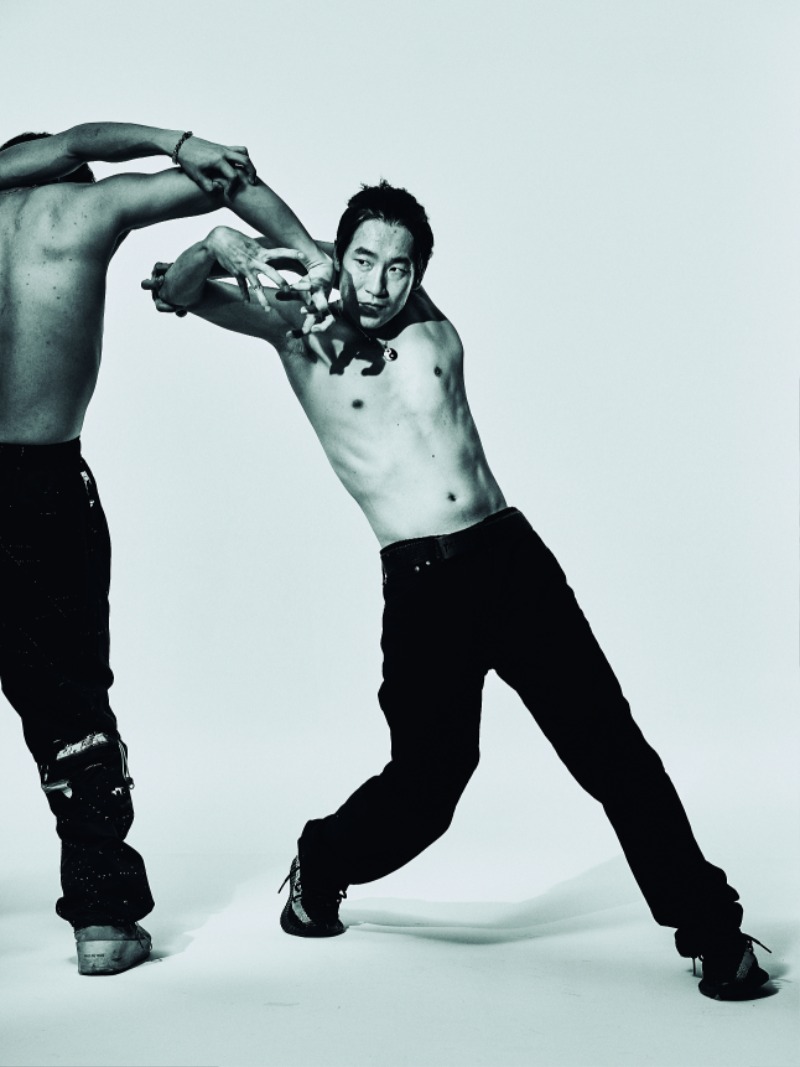

Centipedz, a four-person dance team, is Korea’s first “bone breaking” crew. Jeon Young, the team’s leader and a film choreographer, splits his time between arranging the movements of actors in zombie films and appearing on screen himself. We spoke with him about his widely acclaimed approach to choreographing rabid characters for the screen.

When performing, Jeon Young’s alias is “Undead.” The macabre moniker recalls some of the biggest films he has choreographed. Jeon’s breakthrough came in “The Wailing,” and he quickly moved to the forefront as the choreographer behind the zombies in “Train to Busan,” Korea’s first serious bid at a domestic zombie blockbuster and one of the top-ranked zombie movies globally. Continuing in the horror genre with the Netflix original series “Kingdom” and the movie “Peninsula,” a sequel to “Train to Busan,” Jeon is now regarded as the expert on Korean-style zombies.

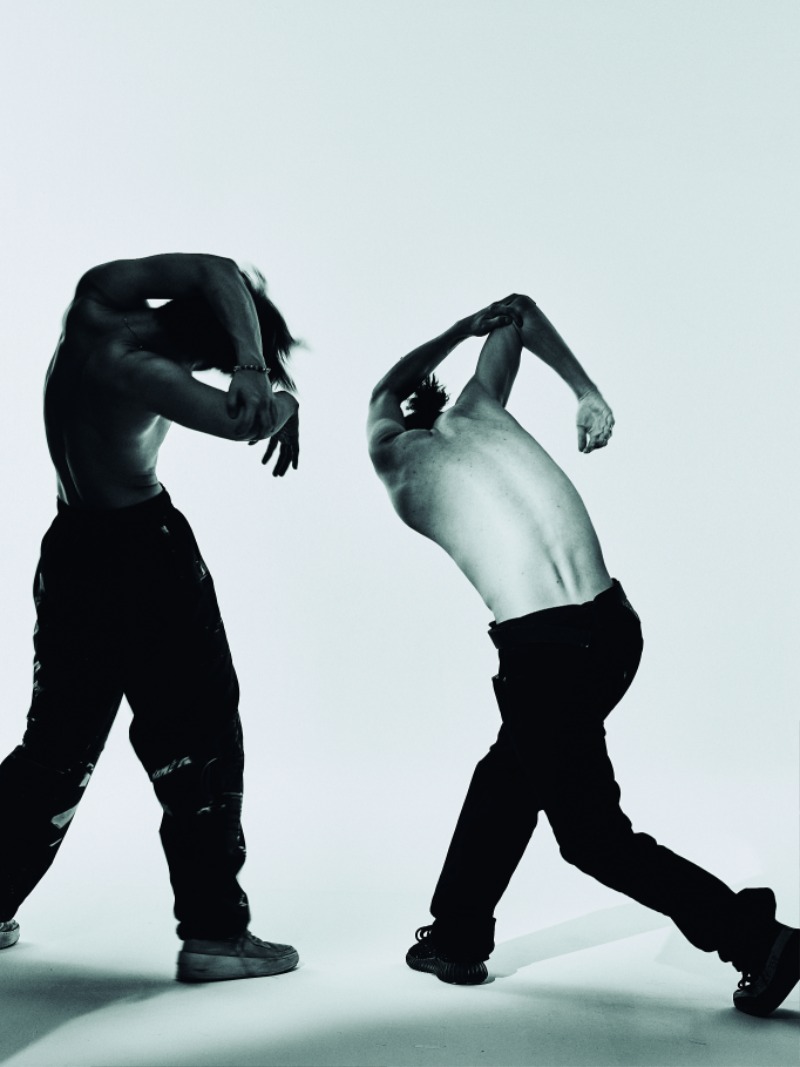

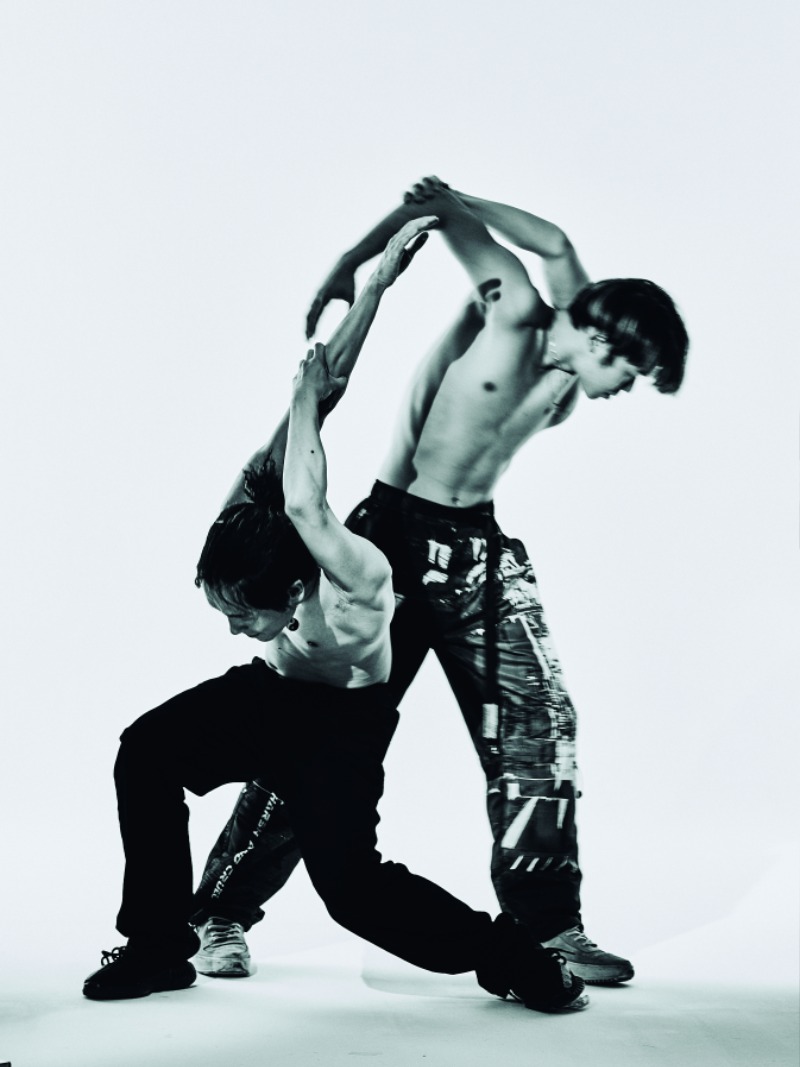

Drawing on his roots as a bone breaking dancer (a dance style also known as “flexing” that resembles the movement of broken limbs), Jeon breathes new life into the limbs of the undead, adjusting his unconventional choreography to the mood of each project. Where the fast-moving zombies of “Train to Busan” run, jump, and flail with the speed of the bullet train, the premodern zombies in “Kingdom” move more like sleepwalkers.

Jeon’s body of work also includes himself. In “Psychokinesis,” a movie about ordinary people waking up with extraordinary abilities, Jeon plays a character with supernatural powers; in “Alienoid” he is an alien locked in a human body and hunted down; and in “The Hunt,” a spy thriller, he is a torture victim. In sum, Jeon is busily leaving traces of himself all over today’s Korean genre films.

Choreographer Jeon Young’s main concern in zombie horror movies is to maximize the grotesque and the bizarre to create a distinct character.

The choreography that Jeon plots for zombie characters fits the movie tempo. For example, the zombies in “Train to Busan” are fast, but the poor and powerless zombies of the Joseon Dynasty in “Kingdom” move like sleepwalkers.

When did you first encounter “bone breaking”?

There’s a dance genre called FlexN that originated in Brooklyn, New York. Bone breaking is one of the elements of that style, and I was immediately drawn to the mechanical movements that were a part of it, which I had never seen before. There are certain physical traits you just have to be born with to make it look like your bones are twisted, and something about that, this feeling that only the chosen few can really do this dance, appealed to me too.

How did you end up becoming a dancer?

I did my best to study hard and work toward a stable career, the way my parents wanted. But my major [administration] just really did not suit me. I was always much more interested in dance and extreme sports. That’s where I was at when I met someone during my military service who was an active member of a professional breakdancing team. The more I interacted with him, the more I realized that I was happiest when dancing.

How did you prepare?

I went back to school to study dance. At the time, I was very interested in breakdancing, but I wasn’t sure where to go from there and had a lot of questions to work through. In the end though, it was YouTube that provided the answer, more so than school. I first came across bone breaking watching videos of dancers abroad, and I felt like this new dance could be the future, so I started practicing. That period overlaps with when I first started working on “The Wailing.”

What led to “The Wailing?”

There was an audition at my school. The other students didn’t show much interest in film work, but I thought it was a cool opportunity to tr y something new with dance, so I signed up. At the audition, I did some breakdancing and some house dance, and then at the end I showed them a little bone breaking, explaining that it was something new I was working on. There was this one move where I twist my body as if I have been hit with an arrow, and at that exact instant I saw the choreographers’ expression change. In the movie, characters writhe and twist from being possessed and cursed, and I think they felt like my dance would be good for capturing those scenes.

How does choreography differ in film and in theater?

I was always curious about how certain distinctive scenes get made, and it has been a real pleasure to experience that whole process while working in the film industry. The actual steps involved in honing my own skills and abilities so that I can better create movements that are legible to audiences have all been a novel experience.

What was your approach for “Train to Busan?”

There are a lot of movies where creatures move in a rhythmical way that has clearly been choreographed by a dancer. But I didn’t want to express the movements of the zombies in “Train to Busan” like that. So, I created movements that ignore rhythm completely. The fact that bone breaking as a genre is focused more on capturing bizarre expressions than beautiful ones made it especially well-suited to the movie.

Jeon and Jeon Han-seung, a member of his team, synched zombies in “The Cursed: Dead Man’s Prey” to move like soldiers drilling, orderly and restrained.

Jeon is mainly inspired by cartoons and games. Sometimes he gets ideas from the mundane such as movements from a machine claw, which he applied to the protagonist in the movie “Psychokinesis.”

What are the challenges in collaborating?

Collaborating with the martial arts team in charge of action stunts required a lot of careful thinking. For example, to show a zombie jump down from something really high and attack a human, it’s most effective to work with the martial arts team and use their wires. At the same time, when you want to show a zombie rolling around on the ground then pick itself up in a strange and uncanny way, it is more effective to use the movements developed by the choreography team. So, collaboration requires consistently revisiting and tweaking who is capable of most creatively showcasing the expressions we need for each part of a sequence.

How do comics and games influence you?

When I was working on “Train to Busan,” I started by studying scenes from the American TV show “The Walking Dead” and the movie “World War Z,” and then tried developing them further. After that I discovered the motif for “Psychokinesis” in the Japanese sci-fi comic Mob Psycho 100, and I came across hints of movements that ended up in the occult movie “The Cursed: Dead Man’s Prey” and in the French horror game “Précipice.” Beyond that, I have also been struck by other games like “Dark Souls,” “Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice,” and “Dying Light.” I get fresh ideas from the movements of different game characters. But ever since my daughter was born, I have much less direct contact with games overall. Now I get a lot of inspiration from watching gameplay videos on YouTube.

Anticipating his eventual retirement, Jeon trains the next generation of choreographers who can build on his body of work and contribute to the development of Korean film.

What differs in graphics?

Well, animations and games have the advantage, when it comes to pushing boundaries. Games in particular use 3D programs to showcase movements that seem impossible for a human to make. Every time I see that, especially as a bone breaking dancer, it feels like a personal challenge.

Any projects in the works?

Currently I’m working on seasons 2 and 3 of the Netflix original series “Sweet Home,” as well as a new TV show for tvN called “Tale of the Nine-Tailed 1938.” I’m also a contestant on Netflix’s survival reality show “Physical: 100.” There are some good scenes in that.

What’s your next goal?

I don’t think any true choreographer just explains things with words. I need to be able to take the movements imagined by the director and actually show them with my own body. Someday I’ll have to retire, and right now there aren’t a lot of other people positioned to use bone breaking as a source of ideas for the movie industry. So, I’m starting to take more of an interest in the next generation and finding people who can carry this on.

Nam Sun-wooReporter, Cine21

Heo Dong-wuk Photographer